Featured Artist: Russell Brower

Three-time Emmy winner and BAFTA-nominated composer Russell Brower has a huge resume, including work as Senior Audio Director / Lead Composer for Blizzard (on World of Warcraft, StarCraft II, and Diablo III, among others), plus work on sounds for Animaniacs, Tiny Toon Adventures, and Batman: The Animated Series. And if none of those hits you as “dream job,” don’t forget his work for Walt Disney Imagineering. That love of sound design and composition has led him to an obsession with synths of all kinds, and a deep trek into VCV Rack for exploring software modular. And he’s got a lot to say about all of it.

Peter Kirn, CDM: You’ve gone equally deep into sound design and composition. How have those worlds connected for you?

Russell Brower: I think sound design and composition have always been inextricably intertwined for me, with my first tangible memory in life being of my mother singing lovingly into my ear as she held me every night for a little while, drifting gently in a big rocking chair before placing me in my crib. Music began as beautiful language to me before I consciously embraced it as an art form.

With no structured or particularly intentioned guidance in these early years, the timbre and expression of a voice, instrument or ensemble was not something I imagined or considered separately from the composition. Therefore, I sort of reinvented every wheel along the way, having only tangential contact with formal training.

Disneyland, located less than an hour away from our Glendale home provided the final two missing pieces… In 1969, the Haunted Mansion opened. I was barely six years old. In the portrait corridor following the “stretching room” I brought the entire moving wave of guests to an abrupt halt next to one of the faux lightning-storm windows. With a gasp, I said, “Listen! Th-the wind! It’s playing the song!” The white-noise-y stormy wind gusts were somehow tuned to the “Grim Grinning Ghosts” melody, and further it was playing in sync with the disembodied pipe organ emanating from the mansion’s walls. (Two decades later, Disney legend Jimmy MacDonald would personally explain to me how he created the effect, which was akin to a guitar “talk-box” process, only using a basketball as an air bladder feeding the tube to his mouth for timbre shaping. I also worked extensively maybe three decades later with his fellow legend Buddy Baker, who wrote the song.)

Then, in 1972, Disneyland debuted the Main Street Electrical Parade, which is when I first knowingly heard a synthesizer. I now knew how I just might be able to realize all the music I heard in my imagination. (Again, later in my career I crossed paths with Bernie Krause, who was part of that original “Baroque Hoedown”-based parade score while working on Disney’s Animal Kingdom, where he guided our efforts to create background sounds of nature which ebbed and flowed over time of day and seasons of the year in non-repeating ways so that the real animals in the park would not become stressed out by loops or inappropriate natural predator sounds and the like.)

Ergo, Step One: get ahold of a synthesizer. Step Three: profit ultimate artistic expression! (Apologies to South Park.)

Where does modular synthesis fit into sound design, especially as you’re working with other electronic media and writing for instruments?

Modular synthesis is sound design. In my experience it is also an analog to orchestration with traditional instruments. Modular was my gateway into synthesizers, sound design, and my entire music career.

My first synthesizer was a PAiA modular which I built from a (ginormous) kit around 1978, and with it I first began to try to imitate the sounds I was most moved by in my favorite recordings. The Moog-y filter sweeps and sparkly bits from the Main Street Electrical Parade were not terribly hard to reproduce, but I was confounded by the inability to create layers upon layers of multitracked parts without painting myself into various corners by simply bouncing between two cassette recorders—but this was all I had until I could afford a Tascam 244 cassette Portastudio in 1982.

I found my ear being drawn away from the relatively spartan sounds of the Electrical Parade and its “Popcorn” era brethren to the detailed, complex, and often subtle masterworks of Isao Tomita’s classical music interpretations. Tomita’s sound design and musicianship was deep and represented to me near-perfect examples of blending great melodic writing with bespoke expressive synthesized and/or processed instrumental or faux-vocal sounds. It blossomed in a way that felt… right.

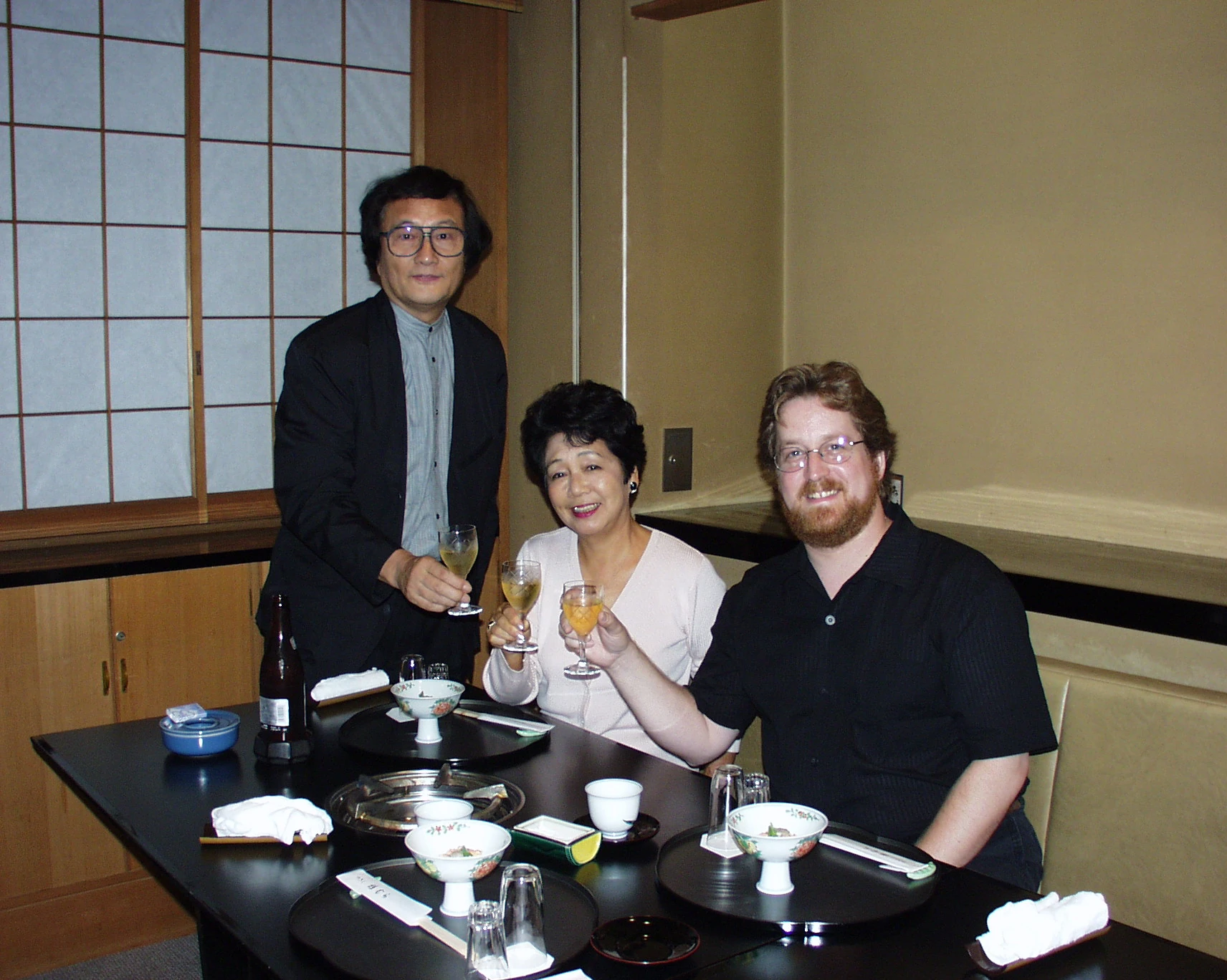

He also had a seemingly endless supply of state-of-the-art synthesizers and professional multitrack recording devices, but none of that stopped me from attempting to recreate the Grand Canyon Suite by Grofé with the PAiA and two cassette decks! I didn’t get too far on that one, but I was learning volumes simply by trying. A few years later, Tomita did his own version of the Grand Canyon, which really pissed me off at the time–! Fortunately, I had the privilege of telling him about this personally when I hired him in 2000 to create an epic original score for the main entrance of the Tokyo DisneySea theme park. He was truly a brilliant and generous artist and became a friend and mentor. Tomita’s original scores are not as well-known in the West as his classical re-imaginings but are just as delightful.

Overlapping my discovery of Tomita’s work, I also became a huge fan of the solo recordings by Larry Fast of Synergy and Peter Gabriel fame. He blended more contemporary rock-era voicing vocabulary with all the power of shorter-form hook-driven original instrumental compositions, which I found equally inspiring. His mastery of studio production and processing as applied to both his solo albums and Peter Gabriel’s early solo outings are worthy of study and appreciation every bit as much today as they were in the late 1970s. (I was on a roll, so I also hired Larry to contribute an album-length track for Tokyo DisneySea in 2000.)

The most important step along my path, however, has been learning to write down the music in my head before getting too specific working with any instrument. I generally begin with jotting down some descriptive words and specific notes on the mood or emotion I want or have been asked to convey. Eventually I will sit down at a real piano – if at all possible; I’ve made do with an iPad and earbuds – to flesh out pitch and melodic ideas. The piano grounds my mind’s ear in reality, and it provides a sort of “vanilla” pitch and interval reference. Once I start playing with samples of specific instruments, it becomes a potential “trap” in which I might subconsciously begin to compose around the limitations of a given sample, or worse still I might inadvertently start writing within the limitation of my terrible keyboard playing abilities!

So I treat the modular similarly, in that I will jot down the pitches and timing (in standard-ish notation) along with reminder-words about the patch I imagined, then come recording time I will patch up the modular deliberately and perform that overdub in its proper context. And if happy accidents reveal themselves as they oft do with modular, I’ll record that, too, and keep it nearby for potential use in mixing or in other sections of the overall project. I also keep a stereo pair of tracks recording whenever I’m patching for pleasure, for the same reasons we all do.

Oh, and actually - let’s talk about your 1978 PAiA rig! What was in it? That was your first synth?

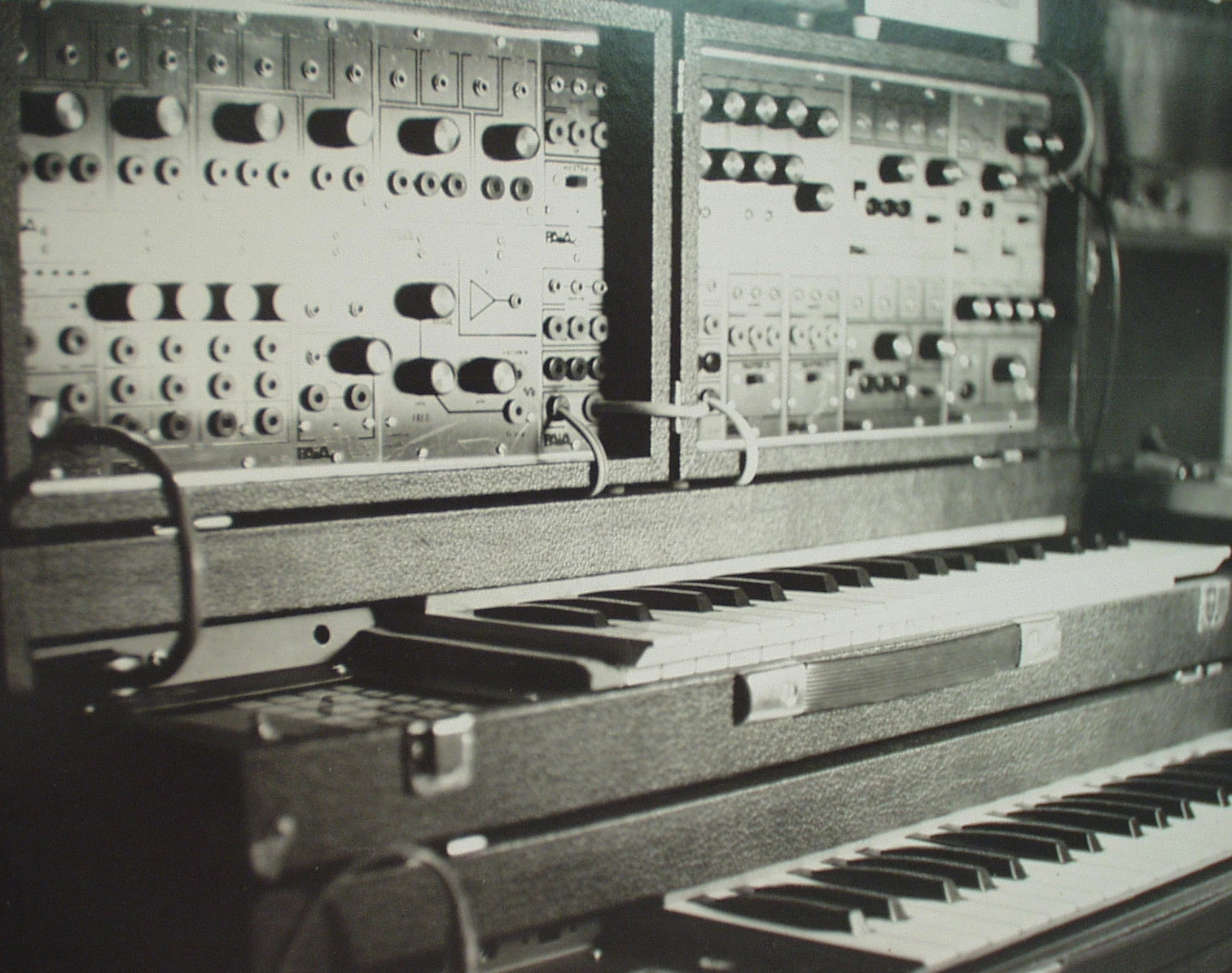

Yes, it was my first! Thanks to a few hundred dollars left to me by my grandfather when he passed, I built a Model P-4700/J modular with the embedded 8700 computer controller, and then the Model 1550 Stringz ‘n’ Thingz top-octave divider string synthesizer during late middle school and early high school. Building them was huge for me, because having a deep, if not at all mathematical or engineering-level understanding of how they worked definitely enhanced my subsequent experiments and explorations. I recall particularly my first couple summers after they were built, during which I truly began to feel like I was growing and constantly in a state of becoming.

Russell Brower’s 1978 PAiA Model P-4700/J DIY modular synthesizer.

Russell Brower’s 1978 PAiA Model P-4700/J DIY modular synthesizer.

PAiA’s founder and chief designer, the late great John Simonton, was another early hero. I only got to speak with him once on the phone, but it’s one of my fondest memories. His “Lab Notes” column from Polyphony magazine constituted 98% of my electronics knowledge. John’s longtime collaborator Marvin Jones, who designed the 1550, is still a friend to this day. I like to consider myself one of the countless success stories from the efforts that wonderful little company made and its role in helping create what is now an immensely larger community of synthesis and modular enthusiasts, although at the time I was just another young synth nerd to them!

What other synths have you had over the years? What’s in your collection now?

Several instruments and pieces of gear have come and gone, but the evergreen favorites are: MemoryMoog – my first commercially-built synth, Oberheim’s Xpander, E-Mu’s Emulators II thru IV, Korg’s Wavestation AD, Casio’s CZ-101, a lovingly-restored old MiniMoog D, and Nord Modulars G1/G2. I had a grey Arp 2600 for a few weeks about 20 years ago, but I had to sell it to pay rent. Ugh.

In recent years, more space and time have begotten new friends: a huge SynthTech MOTM modular (which I also built myself), Moog IIIc modern-era version with Sequencer expansion, Synclavier 9600 (long story and acquired for far less than it once retailed for), a Korg FS 2600 to replace the vintage one, and I don’t know how many HP of Eurorack modules. I absolutely love the format! Also an OP-1 Field, Deluge, Synclavier Regen and the newest addition being an Osmose. Paul Schreiber claims I have the most MOTM modules of his customer base, then Michael Boddicker saw my Eurorack Modular and suggested an intervention might be in order. Coming from him, I suppose I might indeed have a problem.

Russell Brower’s studio during World of Warcraft production.

Russell Brower’s studio during World of Warcraft production.

How did you come across VCV Rack?

You know, I cannot recall where I first saw VCV Rack 1.0, but when I did it was only after several disappointing experiences with other products with similar goals. Most of my gripes related to both the high cost of some, along with various copy protection woes, which after 30+ years of modern software DSP, I have little patience left for!

Imagine my astonishment and unfolding delight when VCV Rack appeared, creating a product, platform, and organically spawning a community. It’s all focused on lowering the friction for musicians of any experience level, requiring only a relatively vanilla computer and zero-to-modest financial investment to get started. And, much like when the iPhone ecosystem opened to outside development, the ability for anyone with access to coding skills and a germ of an idea can start to create their own modules.

Andrew Belt’s contributions remind me a lot of John Simonton and PAiA in a way, except on a modern global scale. Anyone who cares to learn even a little about synthesis for any reason can find a suitable path towards new and valuable skills and experiences without the barriers we all once encountered at nearly every step. The educational opportunities alone are quite impressive.

What sort of patches are you working on?

Patching comes in two categories for me: realizing the sounds I have planned for a specific overdub as mentioned earlier, and the times I just like patching with no pressure and seeing what happens. (I generally don’t attempt experimental feedback networks whilst on a deadline!) Again, I keep a two-track recording of the latter. This is really easy in VCV Rack, and I also have built up several small pods or skiffs of certain Eurorack modules that play especially well with other random sound tools—these are what I’ll grab a couple of and sit on the couch with headphones on, having patching adventures and/or learning new modules. Several of these small units include something like a 4ms WAV Recorder, Disting Mk4, or similar recording device, plus a headphone driver. In this way, most any new module I’m learning or whatever can be recorded with little hassle. It’s also easy to toss one or two of these into a backpack or carryon bag for trips.

I think maybe the theme here for me is that when I’m in a creative mode, I like to reduce the chances that technical issues will rear their ugly heads and kill my mood. Going back to what I mentioned earlier about doing hardcore writing at a simple piano and not a complex synth or workstation, I have come to realize that the one danger my otherwise beloved computer poses is that it can suddenly engage my left brain when the tech goes sideways, and that is something I definitely do not have time for when I’m either writing for my supper or just preferring to remain in a creative “right brain” flow.

Russell Brower at Abbey Road Studios.

Russell Brower at Abbey Road Studios.

Any favorite VCV Rack modules?

My favorites are seriously all the “bread and butter” utility modules we never have enough of in real life hardware, like attenuators, attenuverters, VCAs, logic, mixers, mults, MIDI I/O, direct access to the rest of the software in the computer and the like. Also, I really appreciate the “lifted from real life, legally” modules like Instruo, Befaco, SynthTech, and the Mutable codebase modules—these modules give me everything I enjoy from their hardware counterparts, save for the human interface of knobs, cords, buttons and switches. And despite having put the small modular units together for travel, often I just can’t bring the hardware along, or it’s too cumbersome or risky.

In all ways except for the mouse and keyboard interface, VCV Rack represents a sort of freedom that I’ve dreamt of since I was a very young modular synthesist.

Would you say there’s any overlap in how you approach instruments and how you design with synthesizers or modular synthesis? Is there a way they inform the other in any direction?

Absolutely. In fact, if you had told me back in middle school that one day, I’d expand my horizons and write for orchestra and even conduct my own compositions onstage with live players and audience and travel around the world doing so, I would’ve said you were crazy! The reason this works for me is in no small part due to the fact that learning synthesis, especially on a modular, is not all that different to the ear from the traditional skills of orchestration. Modulars can put emphasis on a sonic “niche theory” of sorts, where at any given moment, you are attempting to find a sound that needs to accomplish a specific thing in a specific frequency range, without muddying the overall picture or obscuring the focus of a piece, even if for only a few isolated seconds. (Bernie Krause has written extensively on the “niche theory” subject in the context of overlapping animal sounds in nature.) Hocketing techniques in traditional orchestration produce aural illusions of evolving timbres, which Wendy Carlos brought to modular synthesis in her seminal album Switched-On Bach. Can you imagine what Maurice Ravel (a.k.a. “the great orchestrator”) might’ve accomplished on modular with multitracking? I suspect Tomita might’ve come close to showing us!

By the way, I’m very excited about the potential the Osmose brings to modular synthesis; this is another application where VCV Rack can handily process a volume of controller messages so immense as to be financially and operationally impractical in modular hardware.

With so much in your career, what are you working on these days?

Placing a greater focus on things much neglected also can and should mean things besides music. A career like this will absolutely impact your personal life, your mental health, your friendships, everything. You’ve got to be okay with this; a career in music has to be something “you would do anyway,” meaning even if you don’t get paid. (And you often may not, although please never work professionally for free. Seriously.)

So in addition to project work, I hope to release music that comes from my heart alone. I have also become intensely interested in mental health issues for all humans, but especially all of us creatives. And while it’s another whole article I won’t go into here, I’ve begun working on myself, learning how my own (somewhat neurodiverse) brain works. If you’re reading this, it’s not unlikely you have experienced things which were extra tough since this creative thing we love doing so much can easily leave us quite vulnerable before the gig is finished. It can be a scary thing or might present as a sort of “writer’s block”. This does not necessarily indicate you’re not neurotypical, yet it underscores how unique, rare and even fragile all artistic gifts can be, and that you owe it to yourself and those you love to find that “life balance” we’ve all heard so much about.

Take good care of yourself, make time for yourself and your family. Sing in the shower. Write music. Design sounds. Create what you would buy or listen to. Meditate. Read Rick Rubin’s book, “The Creative Act”. My happy place is to pull up a couch, a laptop with VCV Rack and patch while surrounded by my family. I let them interrupt at least a few times before retiring to the music cave, and even then, I just smile, knowing that my gear will not be upset if I ignore it in favor of living a full life.

Oh, and “Why Do I Do What I Do?” These days it’s for the occasional joy and privilege of witnessing how a piece of music I created can impact another person in a positive way.

More News

- 2025-03-27 VCV Rack 2.6 released

- 2024-09-07 VCV+: Unlimited access to VCV Rack modules

- 2024-04-21 VCV Rack 2.5 released

- 2023-08-19 Featured Artist: Russell Brower

- 2023-07-01 Featured Artist: Omri Cohen

- 2023-05-23 Featured Artist: Sarah Belle Reid

- 2021-11-30 VCV Rack 2 Free and Pro released