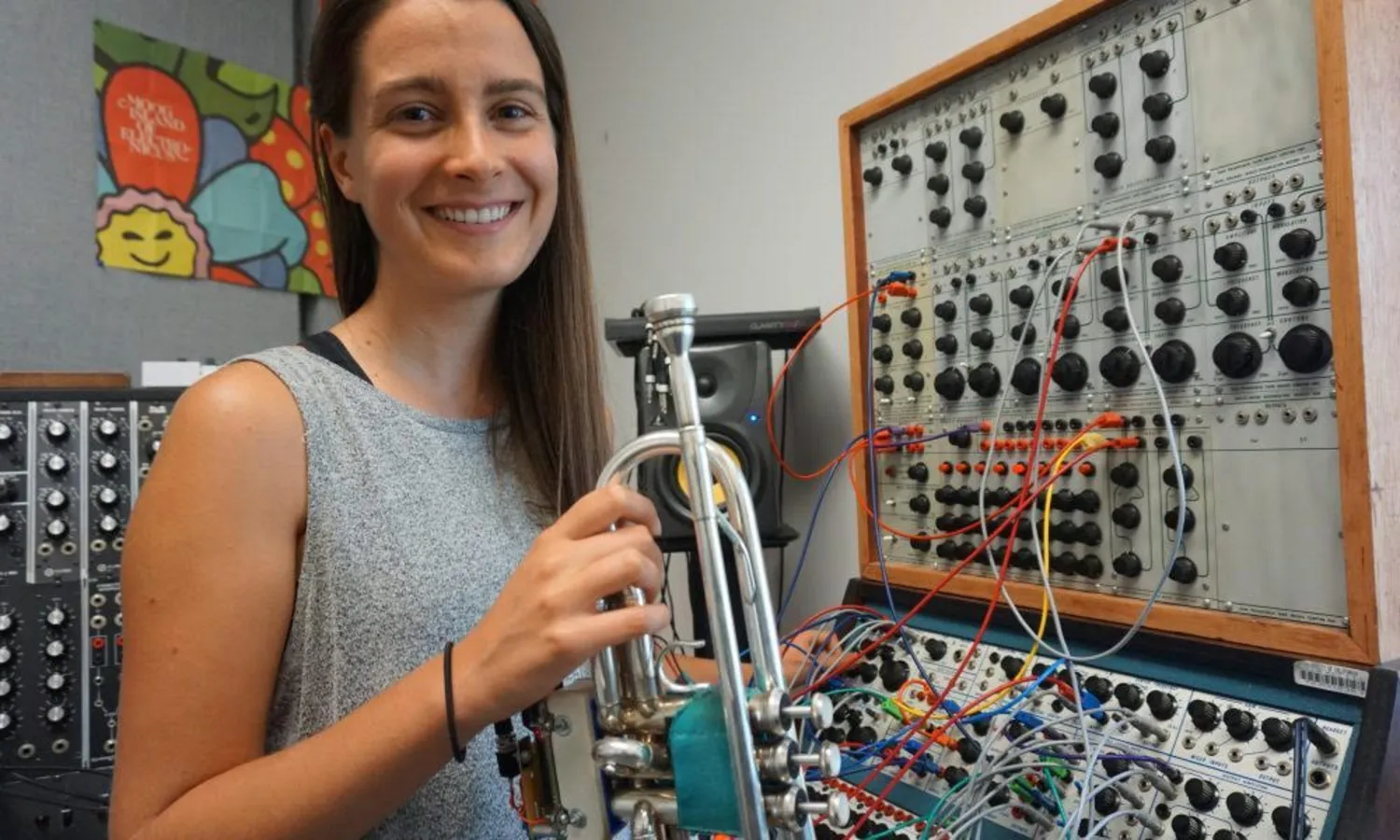

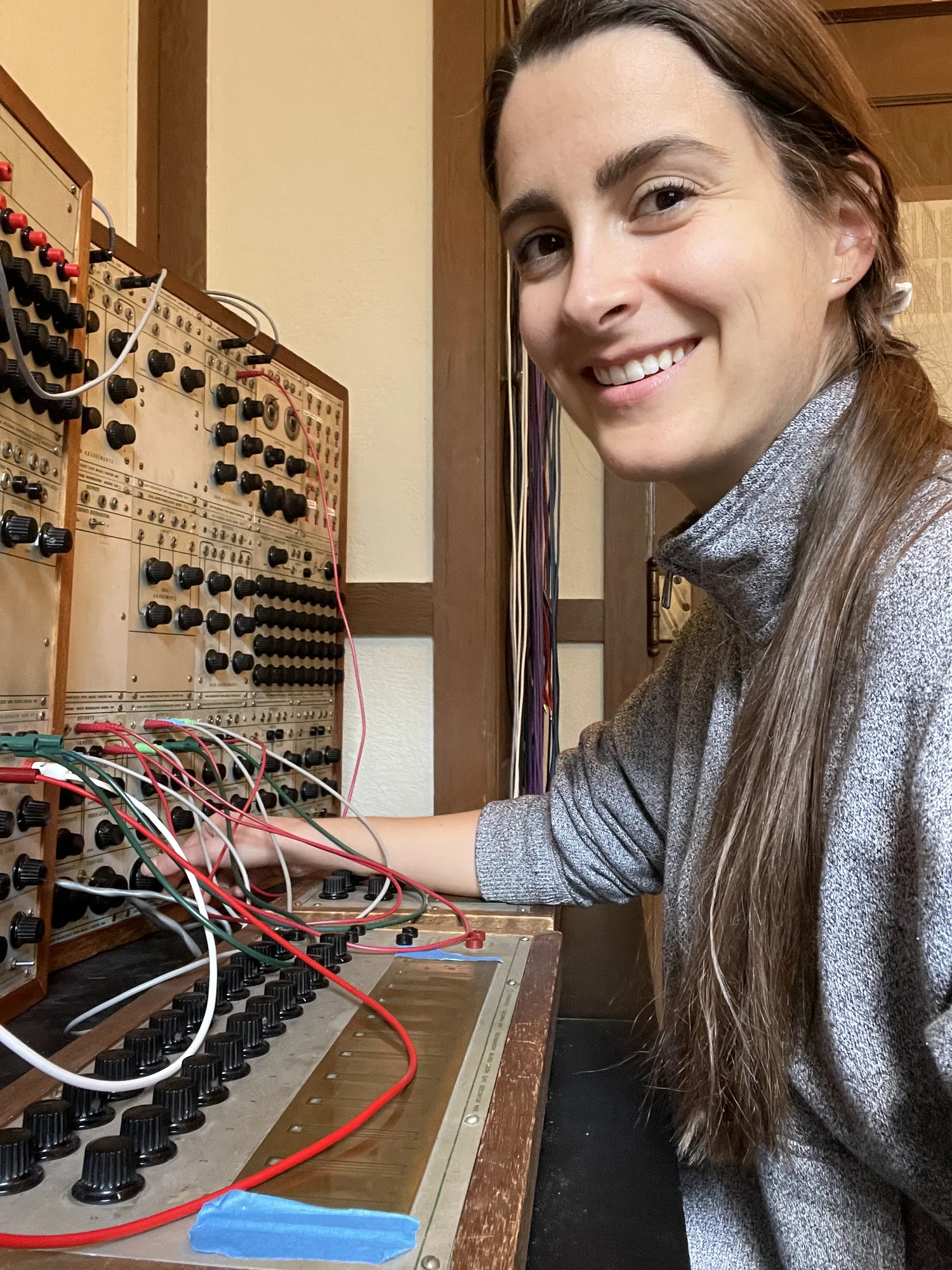

Featured Artist: Sarah Belle Reid

Sarah Belle Reid is the ultimate modular multi-instrumentalist and composer. When she isn’t teaching, scoring, or tweaking, she’s also playing a unique expanded trumpet of her own invention. Dubbed the MIGSI (Minimally Invasive Gesture Sensing Interface), it’s covered in sensors, wires, and lights, expanding the control and expression possibilities of the acoustic instrument. VCV Rack is a tool for composition, sound design, performance, and a way for her to introduce others to the world of synthesis and modular creation. She joins us to share how she works, how trumpet and voice can expand performance, and how she approaches composition, scoring, and teaching.

Peter Kirn, CDM: Having encountered your compositions and hand-built instruments before, I’m curious about how you’re working with modular. What’s the role of modular in your workflow composing or designing sounds? In your live setup?

Sarah Belle Reid: My workflow with modular synthesizers changes a lot depending on what I’m working on, but lately, I’ve really been enjoying approaching modular synths in a couple of different ways:

1. When performing live, I find it really inspiring to consider the modular as a collaborative, co-creative partner, rather than a tool/instrument I have full control over. Improvisation is a huge part of my performance practice, so I really love building patches and interactions on the modular synth that have an inner life of their own—patches that sometimes move with me and respond to me in predictable ways, and other times push the music into surprising, unknown directions. My favorite way to achieve this is by balancing precise hands-on interaction with inherently unstable feedback-driven patching—it creates a really nice dance between chaos and control that I love.

2. Lately, when composing in my studio, I’ve been using modular synths to generate sound material that I then chop up and use as samples in my music. I have always been very inspired by classic tape music composition, and I love the intricacy with which you can construct sound worlds through meticulous splicing, editing, and arranging.

Are you using anything like your MIGSI (Minimally Invasive Gesture Sensing Interface) with modular? Is there anything you do with human interfacing and control voltage, anything like that?

Yes, all the time! With MIGSI, I’m able to extract gestural data from my trumpet as I play it and convert that into control voltage for use in the modular synth.

Even when I’m not using MIGSI, however, pretty much all of my patches incorporate some element of human interfacing/control. In my opinion, interaction is one of the most important things to consider when building a synth patch or designing sounds. Using different interfaces to interact with the same patch on a synth—e.g…, a joystick vs. a keyboard vs. a microphone—can have wildly different results.

The most common form of interaction I use in my work is audio control—using envelope followers and comparators to detect the loudness of my voice or trumpet through a microphone, and using those signals to trigger events within the synth or modulate different parameters of sound; or using tools like fixed filter banks to isolate different spectral regions in external sound sources and use them to modulate or trigger the synth (again, via envelope following).

How did you encounter VCV Rack? Where does it fit in with the other tools you’re using?

The biggest way I use VCV Rack is as a teaching tool. I run an online course called Learning Sound & Synthesis, which teaches you everything you need to make music and design your own sounds from scratch using modular synthesizers. The class covers synth history, step-by-step “how-to” synth patching from the very beginning to advanced techniques, as well as extensive lessons on composing with synths, live performance, turning your sounds into songs, and developing as a musician.

VCV Rack is the primary tool I use in Learning Sound & Synthesis because it is so accessible and flexible for beginners. You can get started for free, learn the fundamentals without ever having to worry about breaking expensive gear, and discover your ideal workflow and favorite types of modules—plus, patches are sharable among students, which contributes to a really open, supportive community and learning environment.

Though my primary reason for getting started with VCV Rack was education, I do occasionally use it in my own creative work these days, and I love it. I travel a lot for concerts and workshops, and my go-to travel setup is a small Eurorack system with either VCV Rack or Max/MSP to supplement with extra control sources and/or sound processors.

P.S.: enrollment in Learning Sound & Synthesis opens two times per year, and more info can be found at https://www.soundandsynthesis.com/. In the meantime, my free introduction to modular synthesis mini-course (also using VCV Rack) is available year-round!

Any favorite modules you want to talk about?

In the VCV Rack environment, the NYSTHI library has a lot of really cool modules that I use a lot—Simpliciter is probably my current favorite for real-time granular chopping / re-arranging of sounds. I also use the Bog Audio Follow and Edge modules in almost all of my patches—they are perhaps not as glamorous as some other options, but SO useful if you’re interested in integrating acoustic sound sources / mic input into your modular synth patches.

What’s the relationship of composition to modular synthesis for you? Does the modular ever inspire compositional ideas for other media? Or how do you see yourself as a composer working with synthesis?

Right now I’m composing an electroacoustic opera that involves a very eclectic ensemble of acoustic instrumentalists (woodwinds, brass, percussion, voice) as well as electronic/electroacoustic instruments and sound sources (modular synths, Max/MSP, daxophone, field recordings, amplified objects, etc.)

The process of composing this work has been very co-creative and cyclical in many ways: I’ll typically start with a simple idea for a sound, melody, or motif, and I’ll explore it in a very improvisational way. Perhaps I’ll build a patch on my modular synth or pick up my trumpet to riff on the idea a bit, or I’ll sketch out a few ideas on paper. From that process, certain ideas and themes will start to emerge and I’ll solidify the ones I like by notating or recording them. From there, I’ll pass notated parts and conceptual prompts over to other players and let them explore the ideas in their own way, often having them improvise a bit off of my starting ideas. Then I’ll comb through recordings, make selections, edits, splices, etc., and build things into a final arrangement, composing and recording new layers or replacing sounds when needed, and so on.

Sometimes the modular synth is where I start with an idea and other times it’s the last thing I add to the arrangement. I love using it as a compositional partner because it’s so tactile and immediate—and yes, it often does inspire ideas for other instruments or projects. Sometimes a single sound will spark an entire new piece.

I know there have been occasional attempts to notate modular synthesis. Do you use any kind of notation, either for yourself or others? Or have you ever had to work with graphical synthesis as a way to represent a modular part?

I typically use a mix of graphical notation (abstract symbols and shapes to represent sound), spectromorphological notation (adapted from Denis Smalley’s writing, as well as Lasse Thoresen’s work on Aural Sonology, a method of analyzing and representing how sounds change over time), traditional Western notation (when specific rhythms and pitches are relevant), and simple descriptive text (to communicate emotional affect or style).

I don’t ever really notate modular synth patches for the purpose of recreating them exactly. Generally speaking, when I’m writing music for other musicians who play electronics, I understand that each player will have their own unique setup that will likely be very different from my own. As such, I focus more on notating the character/quality of sound (using what I refer to as “instrument-neutral notation”), rather than notating the specific patch/set of tools used to create it. This is where graphical notation and spectromorphological notation often come into play in my practice.

I don’t use all of these approaches in every project—it really depends on what I’m trying to communicate to the players or listeners. Ultimately, I’m a big believer that there’s no right or wrong way to “do” notation. Your notation doesn’t have to look like a Beethoven score to be valid! It’s really up to you—whatever helps you express your ideas is the best thing to do.

How do you work with improvisation and modular synths? Does it impact how you work with parameters and assigning knobs? Are you ever improvising with instruments alongside the modular setup?

Typically, when I’m improvising with a modular synth I’m also improvising with my trumpet or my voice. Since I’m already doing so much with my hands, I try to build out interaction in the patch so that I don’t need to be turning knobs while I’m improvising. For me, too much knob-turning pulls me out of listening mode and into technician mode, which isn’t ideal.

So for example, instead of using knobs to control parameters in the patch, I’ll derive multiple different forms of control voltages from my microphone input, and use that instead.

I also really like to play with obfuscating control and interaction, so it’s not always a clear 1:1 relationship. Instead of modulating the primary audio source directly, for example, I might focus on modulating an LFO that’s modulating another control source, that’s, in turn, affecting the primary audio source. Approaching things in this way really helps to create a sense of collaboration between yourself and the modular synth—almost like it’s a duo partner, which is something I really love.

Synth technology can go pretty retro. Are there any directions in synthesis now that excite you, or that take you in different directions than maybe in past decades?

Actually, lately, I’ve been doing some really deep dives into historical synth designs by exploring Don Buchla’s early modules and instruments, and I’m finding tons of inspiration in those. I’ve been especially interested in the Expressive E Touché, and recently had the chance to spend a couple of days with one. Buchla was such a brilliant instrument designer and creative thinker, and his work has become very influential in how I personally approach interaction, patching, and sound design. Despite the fact that all of his instruments are decades old, they still feel very ahead of the curve. Instruments he made in the 70s and 80s are in some ways much more sophisticated than anything that’s available now.

As far as current instrument designs go, I really like the way that Make Noise adopts inspiration from old designs like these, while venturing into new sonic territory. With all the Make Noise x soundhack modules, for instance, I’m able to directly interact with things that previously would only have been possible on a computer. They really change the way I approach some of these more esoteric synthesis methods, which is super exciting.

The world of electronic music and modular synthesis is still, relatively speaking, very young. I personally still find it all pretty inspiring, and probably will for quite some time.

What is the role of synthesized sound in your composition? Do you have a particular way that you tend to begin to work in Rack, specifically? (For instance, how do you build up patches, and how much is sort of assembling versus playing?)

I don’t really have a particular starting point for a patch. In fact, one of my favorite creative challenges is to start somewhere different with each patch, to make sure I’m not defaulting into habits and instead always exploring new possibilities.

Aside from that, the number one thing I consider when patching is interaction.

How do I want to interact with this sound?

Do my gestures start the sound, or stop it?

Do I want it to cooperate with me, or talk back to me? (Or both?)

I find that asking myself questions like these always pushes me in new and interesting directions with my patching. You never exactly know where a patch will lead you, but that’s half the fun!

More News

- 2025-03-27 VCV Rack 2.6 released

- 2024-09-07 VCV+: Unlimited access to VCV Rack modules

- 2024-04-21 VCV Rack 2.5 released

- 2023-08-19 Featured Artist: Russell Brower

- 2023-07-01 Featured Artist: Omri Cohen

- 2023-05-23 Featured Artist: Sarah Belle Reid

- 2021-11-30 VCV Rack 2 Free and Pro released